Does Out-Migration Hurt Canada?

Out-migration means those who immigrate into Canada and then leave the country after any given time period and for any number of reasons. An immigrant to Canada may leave after a certain time never to return, or may return at least once. Is Out-Migration in fact an unfunded liability for the Canadian government and thus for the Canadian taxpayer?

Is Out-Migration in fact an unfunded liability for the Canadian government and thus for the Canadian taxpayer? That’s the conclusion sketched out by Dr. Don DeVoretz, the research director at the Canadians Abroad Project of the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. What out-migration is and how DeVoretz came to these conclusions involves a key policy issue for government officials and Canadians living abroad: what public services does an immigrant to Canada, or a native-born Canadian who emigrates out of the country, consume and what taxes does she or he pay? Especially when the immigrant leaves for their country of birth, or any other country for that matter. The answer is as diverse as Canada’s population, and it bears paying a little attention to the details of work by academics like DeVoretz.

What is Out Migration?

Out-migration, strictly speaking, is merely the migration from one region to another and is thus a synonym of emigration. The sense of the word here, however, is more precise: it means those who immigrate into Canada and then leave the country after any given time period and for any number of reasons. An immigrant to Canada may leave after a certain time never to return, or may return at least once. Out-migration can also occur across generations, with second-generation Canadians sometimes returning to the country of their parents. For example, Canadians return to places like greater China (China + Hong Kong and Taiwan), as well as to a much lesser extent India, to pursue career opportunities or for family or other reasons.

And here we come across an important difference with Dr. DeVoretz’s analysis, which only includes Canadian citizens, whether native-born or naturalized, who choose to leave Canada for at least a year. This is labelled the Canadian Diaspora and is related to, but not the same as, the community of naturalized immigrants to Canada who also choose to leave the country. This is because both groups include naturalized Canadians. But because the groups are not the same – the Canadian Diaspora includes native-born Canadians – the general policy conclusions reached by him are not quite as clear.

Which Immigrants Leave Canada?

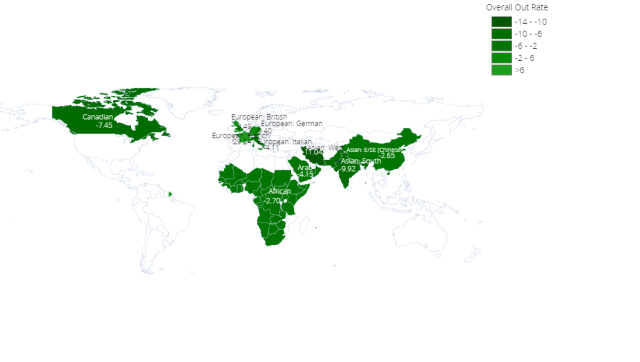

According to a study available on a Statistics Canada webpage, young male immigrants who qualify under the business and skilled worker classes are the most likely to then leave the country. About a third of males from ages 25 to 45 left Canada in the 20 year period following their landing as immigrants, based on findings covering the period from 1980 to 2000. The data confirms this is closely tied to economic cycles: for example those that arrived during the recession of the early 90’s were significantly more likely to leave. Of those that did leave, about half of them did so within the first year of arriving in Canada. The country of origin of these younger, skilled males was also an important factor. The two most prevalent destinations, and country of origin as well, in this study were the United States and Hong Kong. Immigrants from Europe and the Caribbean were only half as likely to leave.

Onward Migrant

Statistics Canada defines the term onward migration as disappearances in a cohort (a specific group of migrants classified by factors like ‘year landed in Canada’) minus reported deaths, estimated deaths and non-tax filers. Essentially, it’s a formula for estimating out-migration, given that Canada does not officially keep records for emigration the way it does for immigration. In other words, it’s another way of defining and quantifying out-migration from Canada. According to a Stats Can study covering the period 1982 – 1997 that classifies onward migration by last country of residence of the migrant, the USA leads the pack at 33%. This may reflect the fact that many US migrants to Canada are professionals who take up managerial positions for a period in the country. Another reason may be that many foreign-born graduates of American engineering and physical sciences post-graduate programs are discouraged by the USA’s H1B temporary visa requirements, and migrate to Canada to seek opportunities. It is possible that these highly skilled professionals later return to the USA when they are able to renew their visa and take advantage of the opportunities south of the border. Northern Europe comes in 2nd at 27%, Hong Kong is 3rd at 23% and Oceana (Australia and New Zealand mainly) is 4th. Taiwan and Lebanon come in at 18%. The rest of the countries on the list of countries that supply Canada with immigrants have onward rates of well below 15%. India and mainland China have onward migration rates of below 10%.

In terms of length of stay in Canada for those who then migrate back to their country of origin, US migrants to Canada tend to stay the shortest, 1 to 3 years, while Hong Kong migrants tend to wait at least 3 years before returning. UK migrants who return home tend to follow US patterns of length of stay, while those from China, Lebanon and Pakistan follow the Hong Kong pattern of waiting at least 3 years. In general, it seems migrants from wealthier developed countries are much less likely to remain in Canada than those from countries like India and China. An important factor here may also be that citizens from India and mainland China who voluntarily acquire foreign citizenship automatically lose their Indian or Chinese citizenship so moving back often means re-applying for citizenship and thus having to choose between Canadian citizenship or their home country’s citizenship.

Migration’s Unfunded Liability

As Dr. Devoretz points out, a Canadian taxpayer starts paying his or her way around the age of 30 until around 65, when many Canadians begin to retire. Over this period you pay more in taxes than you consume in public services – education and health care are the two big ones – and thus allow the government to pay for younger and older segments of the population who consume more than they pay for in taxes. Onward migration, or out-migration, distorts this balance especially if the migrant spends the bulk of his or her most productive work years abroad, and then returns to Canada for their retirement. This is the unfunded liability Devoretz is alerting us all to and it is a certainty his work has been noticed by Minister Kenny and CIC officials in general. There is a problem with applying this analysis to immigrants who then migrate out of Canada, however. Many arrive in Canada already having completed their education abroad in their home country. That means that those public services that a native-born Canadian consumes in childhood and as a student are not in fact consumed by the immigrant who arrives as a young adult. And if the immigrant migrates back to his or her country of origin after having worked and paid taxes in Canada for a number of years, it is arguable that the migrant is a net contributor. What Devoretz seems to be taking aim at are those native-born Canadians who spend a part of their productive, tax-paying years abroad and then return home for their retirement years. His solution, merely implied, seems to be to impose a US-style tax system that obligates citizens to file and pay taxes even when they reside outside of the country. As a Canadian, if you are a Non-Resident, you are currently no longer required to pay taxes. Might that be the Conservative government’s next move? And even though such a measure would be aimed more at native-born Canadians who move abroad – mostly to the US – to pursue career opportunities, it would affect all naturalized Canadians who may decide to migrate out of the country at some point. Would a change in Canada’s tax code impact the flows of out-migration? It may be that the next few years will give all of us Canadians living abroad a chance to find out.